The four-color process using cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK) inks is a relatively new development in the history of printing; It has only been around for about 130 years. Its effectiveness builds on other technological developments like halftoning, offset lithography, and modern ink manufacturing techniques that enable wet-on-wet printing. Before CMYK, reproducing color images was very tedious. In Gutenberg’s time (during the 15th Century), artists were sometimes hired to hand color black-only prints, but this work was time-consuming and expensive. Late in the 18th Century, Alois Senefelder’s development of lithographic printing opened up new possibilities for high-quality (and very detailed) printing, though it was often monochrome only. Around the middle of the 19th Century, pioneering printers began using stone lithography to create multiple colors in a process known as chromolithography. Understanding the tremendous advancements in color printing that took place during that time provides some insight into the technological developments that are happening today.

A Promotional Example of Chromolithography

Some of the most beautiful examples of chromolithography are contained in the “Album des célébrités contemporaines, publié par Lefevrè-Utile” (circa 1909). Translated, the title reads “Album of Contemporary Celebrities, published by Lefevrè-Utile.” This album is a collection of individual promotional cards produced for the Lefevrè-Utile company of Nantes, France. Founded in 1846, Lefevrè-Utile continues to operate today—but you are more likely to know them as LU, a maker of cookies like Petit Beurre. The individual cards shown in the album were included in packages of cookies as a collector’s item. There are only five of these complete albums in America, and one of them is at the Museum of Printing in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Images like the ones in the LU album were popular as trading cards from the 1870s to the early 1900s. People collected and traded the cards and often saved them in albums. Similar in concept are fancy Victorian chromolithographic prints of romantic and sentimental scenes called “scraps,” which featured birds, butterflies, flowers, hands, hearts, pets, wild animals, and many other images. Some of these were also traded or collected in albums.

The Birth of the American Christmas Card

Chromolithography played a big role in the time-honored tradition of sending Christmas cards. A Boston-based lithographer and publisher named Louis Prang (1824-1909) was instrumental in the development of the chromolithographic color printing process. Born in Prussian Silesia, Prang was the son of a textile manufacturer. He learned engraving, dyeing, and printing from his father before emigrating to the United States, ultimately founding a printing company with a partner in 1856. In 1864, he went to Germany to learn about the latest lithographic techniques. When he returned, his company began creating reproductions of well-known art works. He expanded his business into greeting cards for the English market in 1873 and then in America in 1874. He is often referred to as the “Father of the American Christmas card.” You will note that the Prang Christmas cards shown below include embossing and gold metallic special effects.

Advertising and Promotion

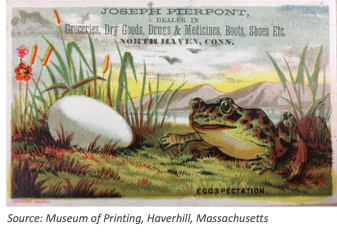

Some chromolithography prints were used for advertising purposes. In the Figure below, an eye-catching image of an egg and a frog titled “Eggspectation” serves as a carrier for the services of “Joseph Pierpoint, Dealer in Groceries, Dry Goods, Drugs & Medicines, Boots, Shoes, Etc.” From a production perspective, it is worth noting that the printer left room at the top for advertising text. This was added afterwards in a separate step using letterpress. This enabled the advertiser to choose the most suitable image from a printer who purchased the already-printed cards from a dealer. This particular card may have survived because of a print flaw. You can see that the black plate is slightly out of alignment. You can also see stippling in the upper right corner, foreshadowing the use of halftoning.

The Next Step Toward CMYK

Experimentation with streamlining the color printing process can be traced back to the work of early chromolithographers, though it took until January of 1893 when a man named William Kurtz printed the first widely reproduced image using a three-color process with blue, red, and yellow inks. Yet the three-color process did not produce a very satisfactory black, and so eventually a black separation (the “key” color and the K in CMYK) was added to solve that issue while also providing detail and contrast.

The Bottom Line

Years from now, what will people remember? Will the inherent beauty or sentimental value of what you print compel them to keep a copy? Unless you’re in the business of book printing or reproducing artists’ work, this may not be the case. Much of what is produced in print today is ephemeral, and that’s okay, but there is still room for attention-grabbing work in printed advertisements, point-of-purchase displays, posters, and other promotional items.

When looking at a classic 19th Century Currier and Ives print of a railroad train or steamboat, you might think that it was produced using chromolithography—but you’d only be half right. The main image was produced using lithography, but Currier and Ives employed a team of colorists who added color by hand. They resisted automation and instead relied on manual labor. That kind of strategy would certainly not work today.

As one examines the rapid advancements in color reproduction between 1850 and 1950, it parallels the more recent technological developments in desktop publishing and digital printing that have totally transformed the industry. The next wave of technological advancements are less likely to be print-related and more likely to come from artificially intelligent uses of content and robotics for automation.

Source: Jim Hamilton, Consultant Emeritus at Keypoint Intelligence

Author bio: Jim Hamilton of Green Harbor Publications is an industry analyst, market researcher, writer, and public speaker. For many years, he was Group Director in charge of Keypoint Intelligence’s (formerly InfoTrends’) Production Digital Printing & Publishing consulting services. He has a BA in German from Amherst College and a Master’s in Printing Technology from the Rochester Institute of Technology.