Two graphic designers comb through thousands of years of iconography in a new handbook for understanding visual language.

In 1914, the cat represented police oppression of women’s suffrage. Today, it represents women grabbing back at the patriarchy. How’s that for mixed messages?

When the graphic designers Mark Fox and Angie Wang started working on a book about symbols in 2011, the sociopolitical realities of 2017 were still over the horizon. Yet in some ways their book, Symbols: A Handbook for Seeing, coincidentally published on November 8, 2016, feels like the perfect guide for an era of cultural upheaval.

Fox and Wang are known for their work with logos, trademarks, and type; both teach at the California College of the Arts and run their own studio, Design Is Play. “We are both practicing graphic designers with a love for the mechanisms by which meaning is conveyed,” they tell Co.Design over email. “We thought that a book exploring symbolism authored by practicing designers would bring a unique perspective to an established category.”

Symbols is a richly illustrated and fascinatingly told visual encyclopedia, organized by themes like “manmade” (bread, hammer) and “animate” (rat, antlers). Each entry is illustrated with examples that span millennia, linking, for instance, the monkey symbology of pre-Columbian Mexico with an 19th-century caricature of Charles Darwin (as a monkey, of course).

It’s not a political book, yet it’s hard, as a reader, to leaf through the book and not be transfixed by the political threads that run through many of its entries. One satirical cartoon from 1903 shows Grover Cleveland’s calm, sunny face (representing “sane democracy”) eclipsed by William Jennings Bryan’s petulant, darkened visage. The book’s entry for “Twins” features a double-profile cartoon of Teddy Roosevelt, both saint and sinner, symbolism that goes all the way back to antiquity. The title of the cartoon, drawn 107 years ago, feels oddly prescient today: “It all depends on the way you look at him.”

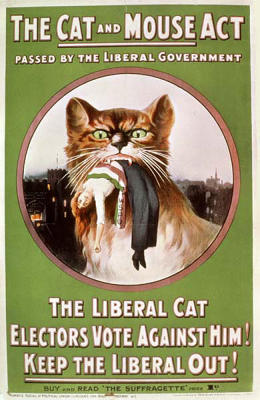

Or take the book’s entry for “rat/mouse,” which features a 1914 poster created by the Women’s Social and Political Union, a women’s suffrage group. The poster shows a vicious cat with a suffragette dangling from its mouth. Accompanied by the phrase “The Cat and Mouse Act,” the symbolism referred to the barbaric treatment of jailed suffragettes at the time, mandated by a parliamentary act of the same name. When an imprisoned suffragette would go on hunger strike to protest her jailing, the police would release her when she got too weak—and then wait until she was recovered to re-arrest her, avoiding public outrage over force-feeding.

A glance at the sea of hundreds of thousands of pink “pussy hats” at the Women’s March on Washington proves that the same symbology is still at work in the women’s rights movement today, yet in a very different way. Instead of the woman as a mouse dangling from a cat’s teeth, the woman embodies the cat—a visual pun—grabbing back at Donald Trump.

The fact that women’s rights activists today are using remarkably similar visual symbols as those of 100 years ago—yet in a completely new way—is a fascinating example of how symbols function in our society. Like words, they’re pushed and pulled and remixed on a nearly hourly bases, yet many of them have remained universal over the centuries. Fox and Wang point to a quote from science writer Ferris Jabr, writing in the New York Times on symbology: “Rather than directly changing the world around us, symbols change the way we perceive it. They extend not our bodies, but our minds.”

Fox and Wang have seen their own work transform over the past few months as the world has changed. Last fall, they created an anti-Trump poster that turned a golden “T” into a swastika, distributing it around San Francisco as an act of protest. “Prior to the election, we assumed that our Trump 24K Gold-Plated posters would be understood by now as a bullet the country collectively dodged,” they explain. The poster is now part of the collections of museums in Warsaw, Zurich, and even the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

But it’s the book’s entry for “hands” that illustrates just how complex and nuanced our visual language is:

The hand signifies agency, the capacity to engender action. A small or weak hand, such as a child’s, signals impotence; an enlarged hand paired with an elongated arm is a sign of power . . . The open hand is receptive and can symbolize peace or submission. The closed hand is unyielding, defiant, and militant: a red, clenched fist was the symbol of the communist Red Front during their years of conflict with the Nazi Party. The American Black Power movement is identified with the fist as well . . .

To understand a culture, understand how it uses universal symbols. In today’s age of radical cultural upheaval, a book like Symbols, though it is overtly apolitical, feels like a necessary companion. It’s a reminder that ultimately the language we use, both visual and verbal, is what shapes our discourse.

This article was originally published in Fast Company.