SVA’s Steven Heller has helped launch dozens of high-profile design careers. To his protégés, he seems like the ultimate insider — but he didn’t start out that way.

Steven Heller is sitting in his office at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts, sipping iced green tea and editing a draft of his latest book. It’s the day before he’s set to give his first design history lecture of the semester to incoming MFA design students, most of whom probably know him as the writer credited in their favorite design books.

Steven Heller is sitting in his office at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts, sipping iced green tea and editing a draft of his latest book. It’s the day before he’s set to give his first design history lecture of the semester to incoming MFA design students, most of whom probably know him as the writer credited in their favorite design books.

For most of his career, Heller woke up around 3:30 a.m. to write. In total, Heller, now 66, has written, edited, or contributed to more than 170 books on design. His steady flow of design journalism paved the way for publications like AIGA’s Eye on Design and Fast Company’s Co.Design, and his work has helped open doors for the modern legion of the industry’s academics, practitioners, and fans. The graduate programs in design, branding, and design criticism he cofounded at SVA serve as a consistent well of young talent who grow into industry leaders. “Design really didn’t have a spokesperson,” says illustrator Marshall Arisman, Heller’s longtime collaborator and friend. “There were articles, sure. But as a constant, as a source? He’s the only one who actually became that.”

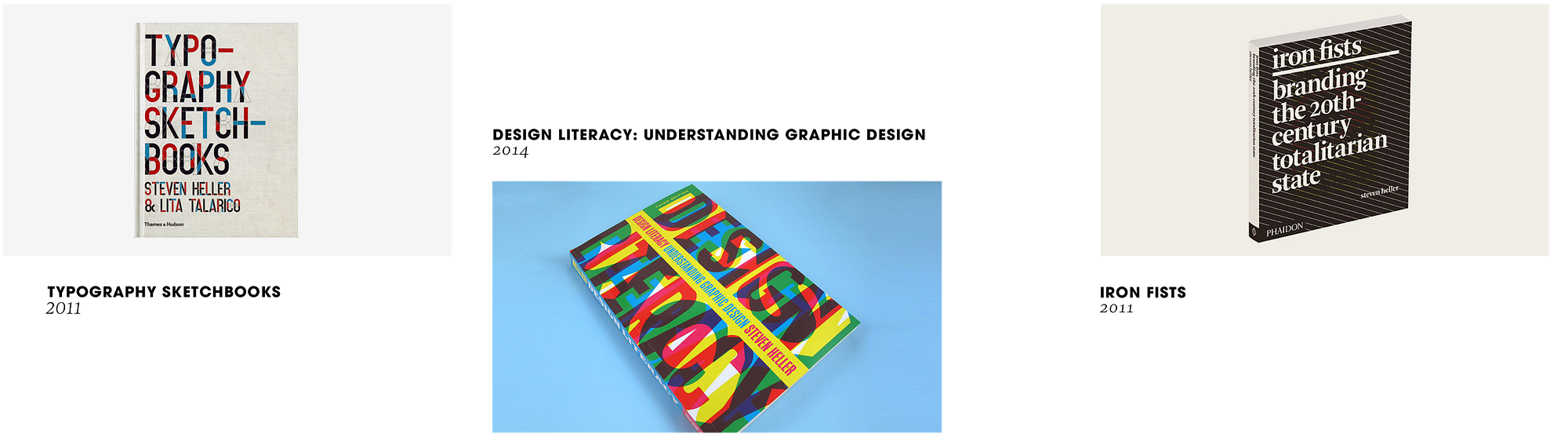

Heller’s books — many of which were written during the three decades he served as art director at The New York Times — have made design accessible to the general public by connecting it to culture, politics, and history. In 1991’s Design Humor: The Art of Graphic Wit, for example, he collaborated with Gail Anderson to show how graphic design can be clever. In 2011’s Iron Fists, Heller’s personal favorite, he created a visual history of propaganda from the most notorious totalitarian states, drawing comparisons between modern corporate branding strategies and the work of Stalin and Hitler’s regimes. The sheer volume of his body of work about graphic design, typography, and illustration has established him as the leader in the field, impossible to ignore.

Heller also has a knack for initiating and nurturing some of the most notable work of his peers and protégés like Debbie Millman, Jessica Helfand, Seymour Chwast, and Maira Kalman. These people are his friends (and his wife, noted graphic designer Louise Fili), who credit him with jump-starting their writing careers and encouraging them to work on projects they never would have otherwise. They are also his students, whose careers in design and journalism might not exist if it weren’t for the design community he’s helped build. “I don’t say no a lot,” he admits. “You just be very friendly and there are some of us who are just friendly back.”

But when you sit with him, as I first did as his graduate student in 2013 and now as a reporter, it’s clear he’s not comfortable with the idea that he’s an industry insider. “What drove me to write so much and work with so many people was imposter syndrome,” says Heller, an educator who didn’t finish college, and a design writer who never formally studied design. “I wanted to prove my worth.” There’s a sense of impatience, as well, with the limitations imposed by age and health, especially after a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in 2007 forced him to adjust his sleep and work habits. “No one knows what they’re talking about when they talk about Parkinson’s,” Heller says of the disease he’s lived with for a decade. “But anyone who has it knows that when you’re stressed, even in a good way, the symptoms are exacerbated.”

Some of his habits have changed since the diagnosis, like setting his alarm clock to the more reasonable hour of 6 a.m. Other habits remain: He’s still churning out books, leading portfolio reviews around the country, writing a daily columnfor Print magazine, and curating exhibits all over the world. At what could be the sunset of an exceptional career, he’s instead chasing an encyclopedic knowledge and body of work that many around him believe he already has.

“In the best of all possible worlds, I wish I would have learned to play the piano, I wish I would have studied guitar, and I wish I could have made movies. I wish I would have gone to school but I wouldn’t have had the patience for it,” Heller says as his gaze, from behind the round-framed glasses that have become his trademark, subtly shift to the clock on my right. “Still, every day is the busiest I’ve ever been.”

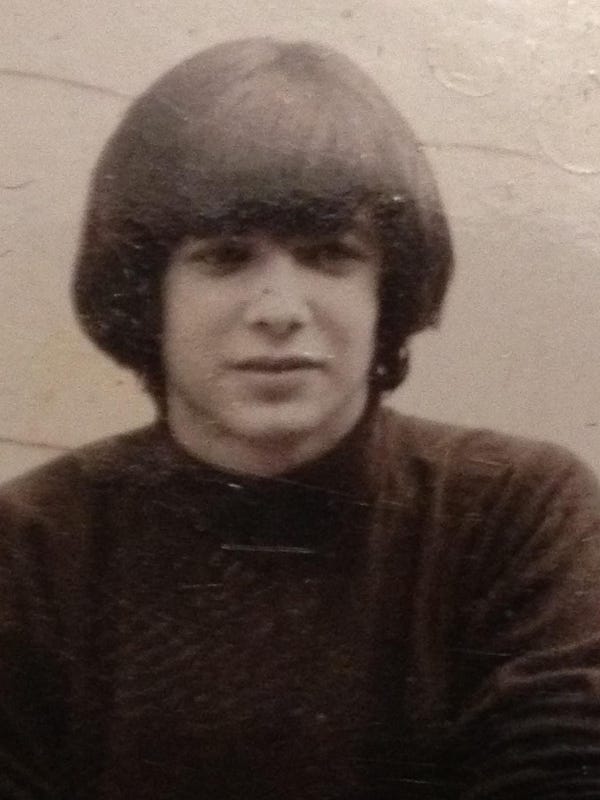

Heller was born in 1950 in New York City. His mother, Bernice, was a buyer for department stores and traveled for work, spending time on the road trend-spotting in other places. Heller’s father Milton was an auditor for the Air Force.

He was politically minded from an early age. At six years old, Heller stuffed envelopes for Adlai Stevenson’s 1956 presidential campaign, hoping to convince New Yorkers to vote for the democratic candidate over Dwight Eisenhower. As a teenager, he skewed even more to the left, inspired by the 1960s counterculture that was bubbling up in Greenwich Village, just a few avenues away from his apartment in Stuyvesant Town.

Heller was the sort of long-haired, rail-thin teenager that Hollywood falls back on as a visual shorthand for the era. He was a freshman at the McBurney School when an exacting dean of discipline sent him to a barbershop (twice) for a school-appropriate cut. On his third strike, the dean had Heller’s head shaved. In embarrassment, he says, he cut himself off from his friends and began seeing a therapist. The following year, worried about their son’s emotional state, Heller’s parents transferred him to the Walden School, a progressive place filled with the children of celebrities and teachers who let students call them by their first names. This is where Heller started drawing.

Heller’s early illustrations were filled with sex and death and lanky figures hanging off crosses. Looking to get his work published, Heller took his portfolio to Dick Hess, the art director of The Evergreen Review, an underground quarterly known for publishing the illustrations of Tomi Ungerer and the writing of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. When the 15-year-old returned to the Evergreen office one week later and noticed that his portfolio hadn’t been touched, it took him years to get up the courage to try again. But, eventually his illustrations were printed in Avatar and Rat, other underground publications of the era. At 17, he became the art director of the New York Free Press.

Each underground paper in 1960s New York City had a distinct niche, yet were all at the mercy of mobsters who were holding the purse strings and readers who wanted to see skin. Heller’s stint at the Free Press lasted about a year, until it couldn’t stay afloat with its very unsexy coverage of city affairs. He then became a cofounder and art director of the New York Review of Sex & Politics, a gig that lasted until he and other staff members were repeatedly arrested as “pornographers” — pawns in the police effort to disrupt mob operations by putting publishers out of business. With that, NYRS&P folded and Heller became the art director of porn tabloid Screw, a job he’d hold for two years before making his precocious move to The New York Times.

Heller landed the day job that occupied the majority of his career — art director of the The New York Times Book Review — at a party. He was 23 years old and bumped into Ruth Ansel, the first female art director at The New York Times Magazine. After seeing his portfolio, she wanted to hire him, but Louis Silverstein, the newspaper’s design director, wanted to put Heller to work on the op-ed page to replace departing art director Jean-Claude Suares. Ansel struck a deal with Silverstein: Heller could be art director of the op-ed page as long as he also contributed to the magazine on a regular basis.

“When I first started working at the Times and the imposter syndrome was at its peak, I had to do a lot of stuff to offset how I felt,” he says. The notion that two famed art directors would bicker over a 23-year-old who was best known for his work at an underground sex magazine is just as puzzling today as it was 43 years ago. But both Ansel and Silverstein were risk takers, and Heller benefited from their willingness to take a chance on him, making a long-term investment in young talent rather than recruiting a seasoned art director from a competing publication.

After three years, during which he worked directly under Silverstein, Heller was promoted to art director of the Book Review and continued to commission the work of illustrators like Milton Glaser, Ed Lam, and Seymour Chwast, returning again and again to the artists who could build conceptually on his ideas. “I couldn’t design a beautiful page and I couldn’t create a beautiful drawing but I could get the people to do those things and give them guidance because I knew what I wanted,” says Heller.

Heller spent nearly every day in the newsroom, arriving at 5 a.m. to work on books and other projects. At 8 a.m, he would open his office for portfolio reviews, never forgetting how he felt when Hess overlooked him at TheEvergreen Review. The reviews would often last no longer than 10 minutes; if he liked what he saw, he’d offer the illustrator a shot to work with him.

The job continued this way until 2007, when Heller began planning his departure from the Times. The decision was partly his and partly that of Sam Tanenhaus, the Book Review’s new editor. Both agreed that after doing the same job for nearly 30 years, Heller wasn’t the right person to give the Book Review a major overhaul. As he transitioned out of his position and began planning for life after the Times, the changes caused an unprecedented level of stress that he believes either triggered or exacerbated his Parkinson’s.

Heller’s known as a gifted art director, but perhaps has an even keener eye for recognizing designer’s talents and skills before they do. “I call Steve my fairy godfather,” says Debbie Millman, a graphic designer, writer, and host of the podcast Design Matters. “He has had more influence on my life than anyone else.” Millman first met Heller in San Diego when he was the master of ceremonies and she was a participant of the 2004 HOW Design Conference’s take on the cooking show Iron Chef, where noted designers would create work in front of a live audience. After the event, Millman — who considered Heller the most famous design writer in the world — invited Heller to lunch. She was so nervous that she made a cheat sheet in case she ran out of things to talk about. A few months later, Millman received a call from Allworth Press. Though she had never written a book before, the publisher was reaching out because Heller had recommended her. The result, How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer, became the first of Millman’s six books.

Heller and Millman also cofounded SVA’s graduate program in branding (the world’s first) and stood together on the commencement stage when the first class graduated in 2011. “He’s one of the most influential design thinkers, period—not just as a writer,” Millman says. “As a curator, as an art director, and as a creator of design education.”

Heller’s long relationship with SVA began as a way to avoid the Vietnam War draft. It was during his alternative newspaper days and Arisman, then the chair of the illustration program, knew he was overqualified to be a student. But, he agreed to admit Heller as long as he went to class. He didn’t — and Arisman kicked him out after one semester. “Finding myself in the SVA context was interesting, but being a student was never my cup of tea,” says Heller. “Starting programs was one way of getting my ideas out.”

Heller would’ve likely flourished in the graduate programs he created, had he had the patience to be a student. In 1984, he encouraged Arisman to establish the master’s program for illustration at SVA—the graduate version of the program he had been kicked out of years earlier—and taught the history of illustration there for 14 years before cofounding the MFA in designwith Lita Talarico. In 2008, Heller established the MFA in design criticism program with Alice Twemlow.

Both the design and design criticism programs created homes for students who wanted to enter the design field in ways that didn’t necessarily require becoming a designer. Rather than building cookie-cutter programs, Heller made way for non-designers who didn’t have an established industry path. His programs also offered traditional design skills to students who wanted commercial uses for their passions, hoping to become entrepreneurs rather than cranking out bland corporate work. Heller’s former design students include Deborah Adler of Adler Design and Jennifer Kinon, who was most recently the design director for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. Design criticism, which in 2015 was rebranded design research and writing, was the first graduate program in the nation to focus on writing about design and nurturing a community of design writers and curators. It gave time and space for graduates like Anne Quito, Quartz’s first design reporter, and the four founders of global editorial consultancy Superscript, to find their footing.

“By continuing to write and encouraging writers so much, he is really at the epicenter of the design-writing movement,” says graphic designer Jessica Helfand, the cofounder of Design Observer, a website that curates design journalism and offers intimate essays from noted design writers like Rick Poynor, Michael Bierut, and of course, Heller himself.

Helfand got her start writing in the early ‘90s when Heller, then the editor of the AIGA Journal of Graphic Design — one of his many side projects — wrote to her and encouraged her to submit story ideas. She had just graduated with a master’s in design from Yale and was working as the design director at the Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine. “The idea you could be a design historian and not be stuck in the dust, that you could actually be an educator who worked in the archives and a designer who excavated unusual things you found as you traveled around the world — it had a huge impact on me,” says Helfand. She says that Design Observer, which she launched with her husband William Drenttel, was a product of many conversations with Heller about design, journalism, and what dictates valuable discourse.

Heller smiles at recollections of how much the design world has evolved through the friends he has made, but takes no credit for their successes. “My friends are much more interesting than me,” he says, “I’ve just always been trying to catch up to them.”

Heller is still one of the most productive people in the field, by any standard but his own. He’s also incomprehensibly generous with his time. Since I’ve known him, he’s never taken more than 46 minutes to respond to an email, but he admits that habit is really just one of his methods of tempering anxiety. It’s his strategy for both completing tasks and maintaining calm, just like his tendency to intentionally lose track of how many books he’s working on.

The blend of impatience and insecurity that has pushed Heller throughout his career hasn’t stopped, but it has matured. Heller now has a vision for how things could and should be. His career gave Adler the opportunity to design the modern prescription medicine bottle; it gave the members of Superscript a place to find one another and build a design community around events like the Architecture and Design Book Club and an exhibition at the Venice Biennale; it presented Millman the opportunity to write that first book and found the MFA branding program. If it weren’t for him, the engaged and diverse design community we have today would be decades out of reach.

Even still, he’s looking toward the future. “I don’t want to keep doing the same thing over and over again,” Heller says. “And I haven’t quite figured out what it is I want to do.”

After following this man for years it was exciting to see this post on Medium.

Mariam Aldhahi

writing about design and tech at Magenta.